This is part of the Top 40 of Sliabh Luachra project, an admittedly flawed and limited endeavor based on entirely subjective criteria. Please leave a comment if you have any questions, thoughts, protests, threats, etc, and click on the irishtune.info links for more information on each tune.

The playing of slow airs is often considered the final great challenge for a traditional Irish musician. It calls for some technical skill, a deep understanding of the material, and a great deal of good judgement. In Sliabh Luachra, airs are an important part of the repertoire. A number of them have become particularly associated with the region, primarily through association with Pádraig O’Keeffe and his pupils. Dozens of airs can be found in O’Keeffe’s manuscripts—many more than he recorded; probably many fewer than he played—and they were a hallmark of his repertoire. They are usually (though not always) the melodies of particular songs. Because of this, there are references to songs in this list, but the song repertoire itself lies outside of the scope of my knowledge at this time. However, here are some sources for songs associated with Cork and Kerry. (Perhaps in the future, if there is a demand for it, we can get a guest expert to suggest a list of top hit songs of Sliabh Luachra.) Because of the close association, the playing of instrumental airs is stylistically informed by singing. In Our Musical Heritage, Seán Ó Riada enumerates a variety of techniques employed by sean nos singers, and they could also be applied to one’s air playing:

“Perhaps the most obvious feature of the West Munster style is its development of rhythmic variation. Where rhythmic variation occurs in other regions, it usually consists in lengthening or shortening a note or group of notes and in retarding or quickening the temp of a phrase or group of phrases; also in changing the accentuation or altering the rhythmic relationship of the notes. In West Munster, however, rhythmic variation is extended by means of a glottal stop , or click. The voice is shut off, as it were, in the middle of a phrase , or even at the end of a phrase. […] Apart from the glottal stop, two other methods of variation are employed, involving dynamics and tone production….The singer may draw special attention to a phrase, or even a single note, by singing it softer or louder than the surrounding notes. And he may draw special attention to a note or group of notes by producing the tone in a particularly nasal fashion.”

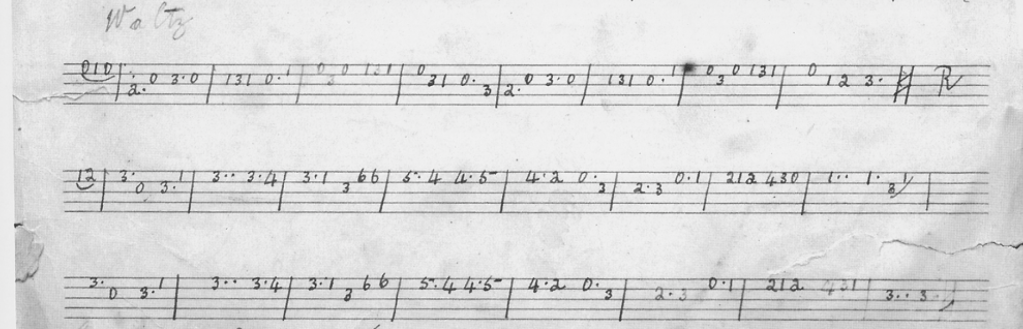

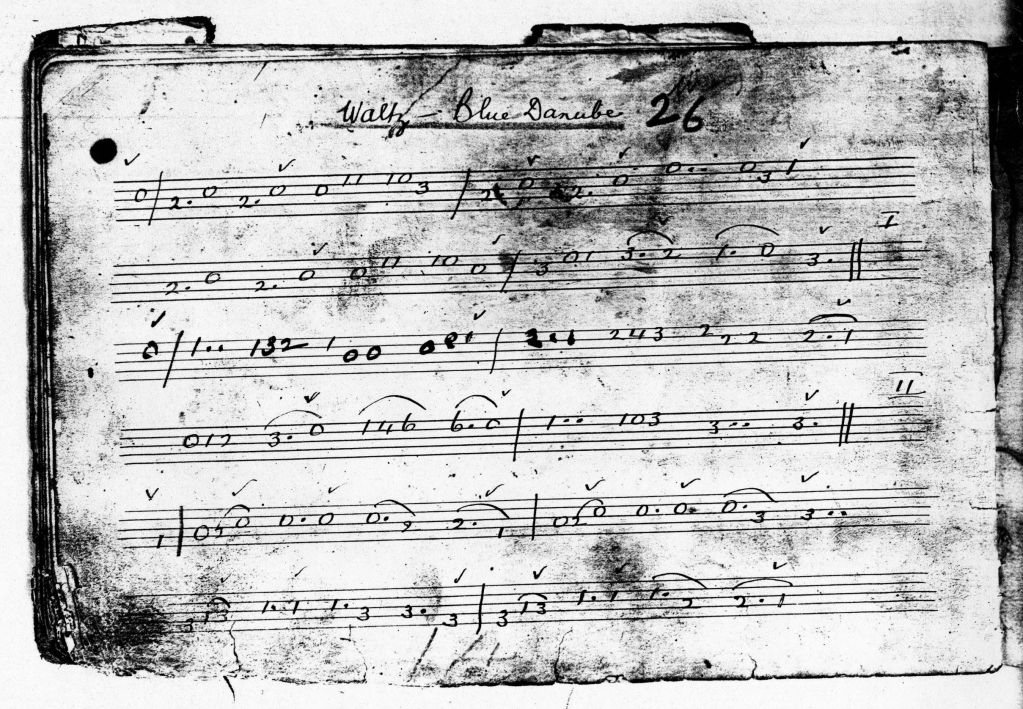

I’ve also included waltzes in this list, as they also stand apart from most of the other dance music forms, being played for couple dancing instead of quadrilles (except in the case of the Waltz Cotillion and maybe other sets I’m not aware of.) Additionally, a number of them can be considered airs in a way, being the melodies of songs played without the words, except in a regular meter instead of freely. These days they are not especially popular compared to other tune forms, in Sliabh Luachra no less than in other regions. O’Keeffe was never recorded playing a waltz (that we’ve discovered yet!) and perhaps he included them in his teaching manuscripts only begrudgingly, as an easy form for beginners. Interestingly, representing an older generation, the John Linehan and Corney Drew (or William Fitzgerald?) manuscripts reproduced in Dan Herlihy’s book Sliabh Luachra Music Masters, Volume 2, are full of airs and waltzes! A few notable Sliabh Luachra musicians have been known for making waltzes a speciality, and so there are a number of waltz tunes that are now particular to the region. In the course of this research it seems to me that most of the waltz playing occurs to the east of the Blackwater, which could be a reflection of the dancing traditions there, or maybe it’s down to the personal tastes of influential individuals.

CONTENTS:

The Banks of the Danube

The Banks of Sullane

Bean an Fhir Rua

The Blackbird

The Blue Danube

The Bluemont

The Bold Trainor

Brosna Town

An Buachaill Caol Dubh

Caoine Uí Domhniall

Caoine Uí Néill

Créde Ó Chiarraí Luachra

Denise

Farewell to Dónal Óg

Ger Dan Mac’s

I’ll Meet You On a Day That Never Ends

Johnny Mickey Barry’s

O’Keeffe’s

Lament for O’Sullivan

Marysheen Went to Bonáne

Moonlight on the Yellow River

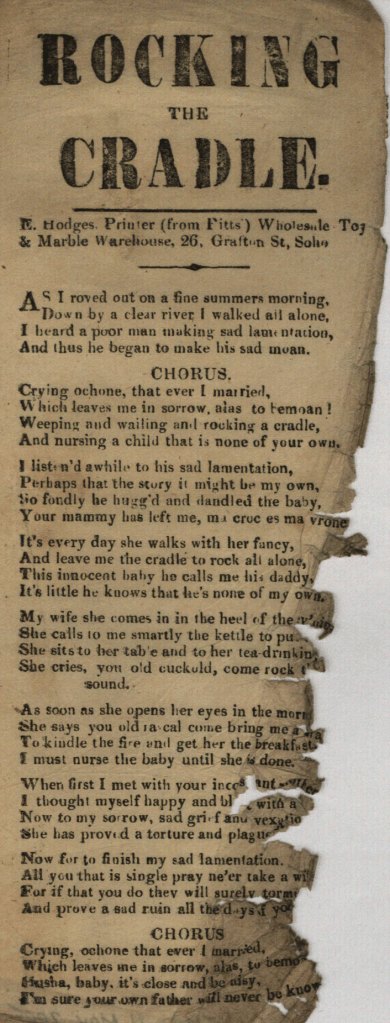

The Old Man Rocking the Cradle

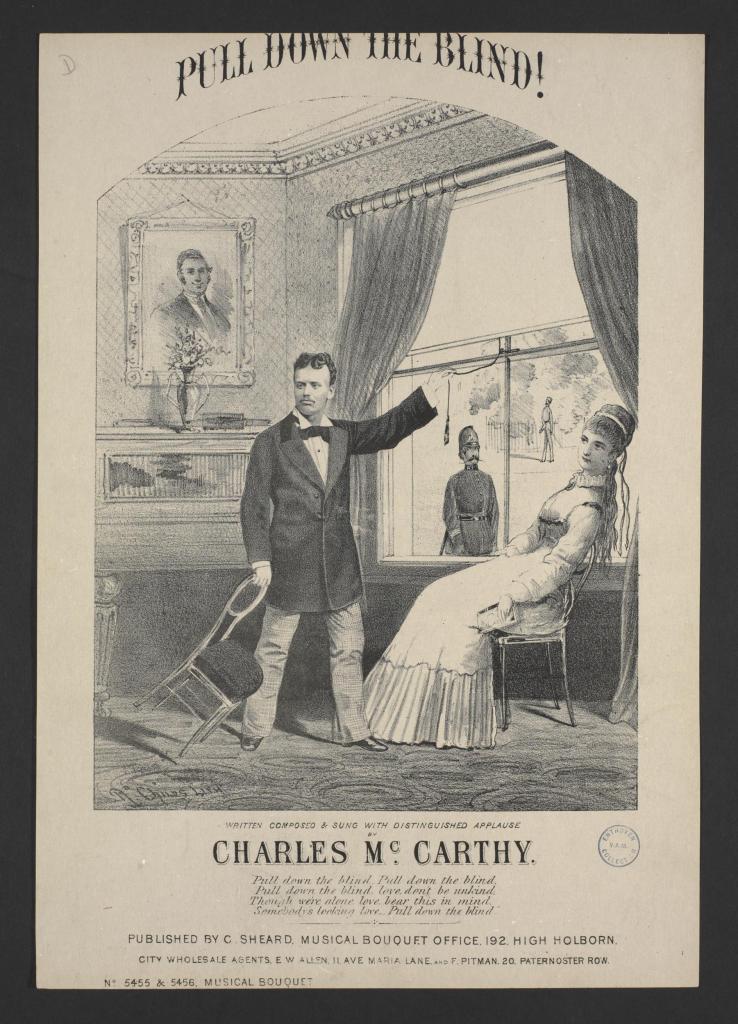

Pull Down the Blinds

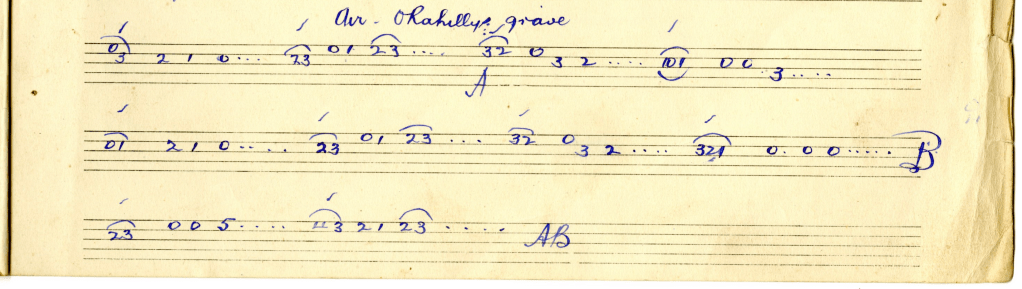

O’Rahilly’s Grave

An Raibh tú ag an gCarraig?

The River Maine

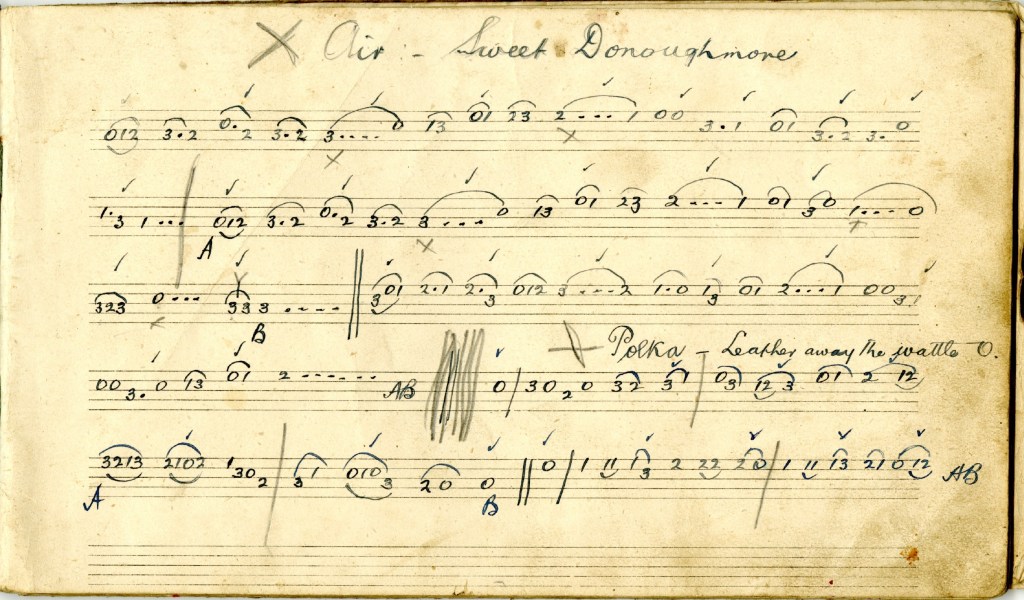

Sweet Donoughmore

Sweet Kingwilliamstown

Tadhg and Biddy

Táimse im’ Chodladh

Ag Taisteal na Blarnan

Terry Lane’s

Tom Billy’s

The Banks of the Danube

https://www.irishtune.info/tune/2952/

Also known as The Wounded Hussar, Captain O’Kane, and (delightfully) Small Birds Rejoice. The air as Pádraig plays it is derived from a melody thought to have been composed by O’Carolan, but it had changed quite a bit by the time it got to Kerry! O’Carolan penned the tune in honor of one Captain Henry “Slasher” O’Kane of Antrim, possibly an Irish cavalryman (for whom the term Hussar is reserved) in the British army, who was said to have died “on the banks of the Danube” (that is, somewhere in Germany or farther east) after a long and distinguished service. As such, the air falls into the category of lament, and is given a properly somber treatment by O’Keeffe. The connection to the goddess Danu (who lends her name both to the majestic river on the continent, and the mountain peaks known as The Paps, a distinctive presence in County Kerry) is mostly coincidental, but serendipitous. A song in English was written to the Carolan melody about a century later by the Scottish poet Thomas Campbell, also in honor of The Wounded Hussar. The Birds title comes from a Robert Burns song set to the same melody.

The Banks of Sullane

https://www.irishtune.info/tune/119/

Maybe not strictly Sliabh Luachra, but borrowed from the rich song tradition of neighboring Muskerry. An Súlán (The Sullane) is a river in County Cork which flows through Cúl Aodha, in the heart of the Cork Gaeltacht, and then through Macroom before joining the Lee.

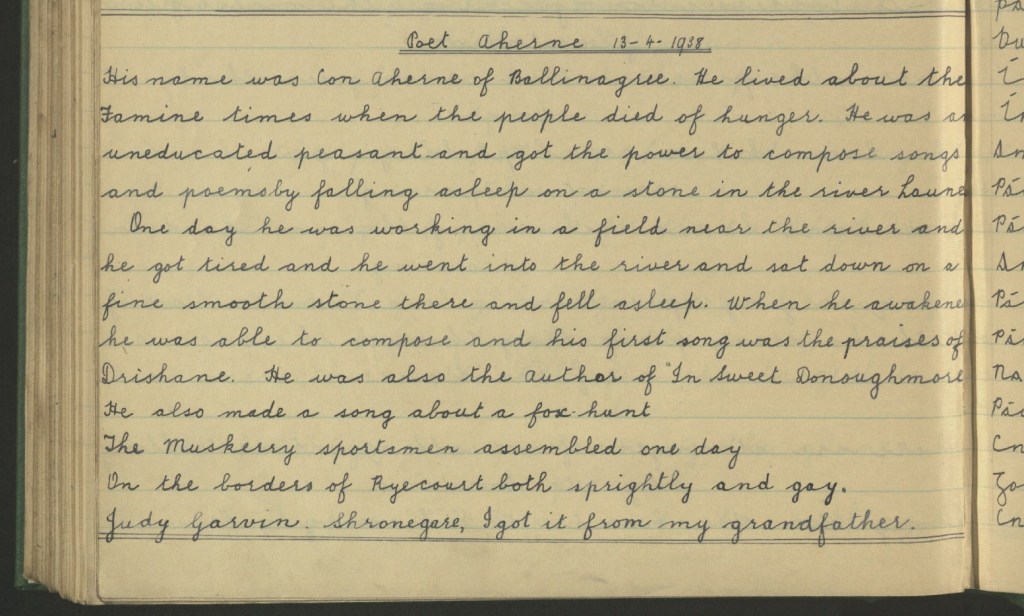

Jackie Daly recorded this air (which is quite similar to that of Cailín Deas Cruite na mBó) on his first solo album in 1977, but the earliest sound recording is Elizabeth Cronin of Ballyvourney who sang it in 1947. According to her son Sean, “The poet Aherne from Clondruhid composed this, I think.”

This Poet Aherne is a pretty obscure character but a few mentions can be found on the invaluable duchas.ie. Collected from Judy Garvin of Scronagare in 1938: “His name was Con Aherne of Ballinagree. He lived about the Famine times when the people died of hunger. He was an uneducated peasant and got the power to compose songs and poems by falling asleep on a stone in the river Laune.

One day he was working in a field near the river and he got tired and he went into the river and sat down on a fine smooth stone there and fell asleep. When he awakened he was able to compose and his first song was the praises of Drishane. He was also the Author of ‘In Sweet Donoughmore.'” This last sentence is interesting… see the entry further down for Sweet Donoughmore.

Another Duchas informant wrote: “Poet Aherne lived in the farm house now occupied by John Goggin, Carrickthomas, Ballinagree. He died, about 73 years ago [the entry is undated which makes this hard to estimate, but I think this comes out to the mid 1850s or 60s]. He was buried in Aughabollogue on a Sunday evening. Con Coakley of Rahalisk who supplied the following poem was at the funeral. His mother was buried in the same place two days later. She was dead when the mourner’s arrived from the poet’s funeral. The year was a very dry one and famine raged mercilessly through the glen. Death visited every house in the place. The poet was aged about 40 when he died [born around 1820, then]. He was a very hard worker with the spade and shovel and always worked by himself. He was of a very serious turn of mind. He was never gay or airy in any way. He was always making rhymes when at work. Canon Pope said that it was a pity his poems were not all written down as they would be worth thousands of pounds He is reputed to have written several poems about Ballinagree but no one living there now can quote them.”

It was early on a bright harvest morning, I strayed by the banks of Sullane

To gaze on such beauties of nature As grace every woodland and lawn

Oh the prospect was surely enchanting, As gay lassies in juvenile bloom

Promenaded by the banks of that river That flows by the town of Macroom

I being airy and fond of recreation To the river(side) I ventured to rove

When weary of rambling and roving I sat myself down by a grove

I sat there some time meditating Till the sun its bright rays had withdrawn

And a damsel of queenly appearance Came down by the banks of Sullane

I stood in great joy and admiration And accosted this damsel most fair

For to me she appeared like Venus Adorned with jewels so rare

Were I ruler of France or of Prussia Oh It’s with me you’d soon wear the crown

And I’d join you in wedlock my darling You’re the beauty of sweet Masseytown

We walked and we talked on together Inhaling the bright pleasant air

Until in a voice most alarmed She said “See – my father goes there!”

His presence to me was appalling With his cross angry look and his frown

Which pierced through my heart like an arrow On my way back to sweet Masseytown

And its now I’ve retired from my roving With a heart full of sorrow and grief

There is no one on earth can console me Or give me one moment’s relief

I will roam through the African Desert Until death summons me to my tomb

For the sake of that charming fair Helen That I met near the town of Macroom

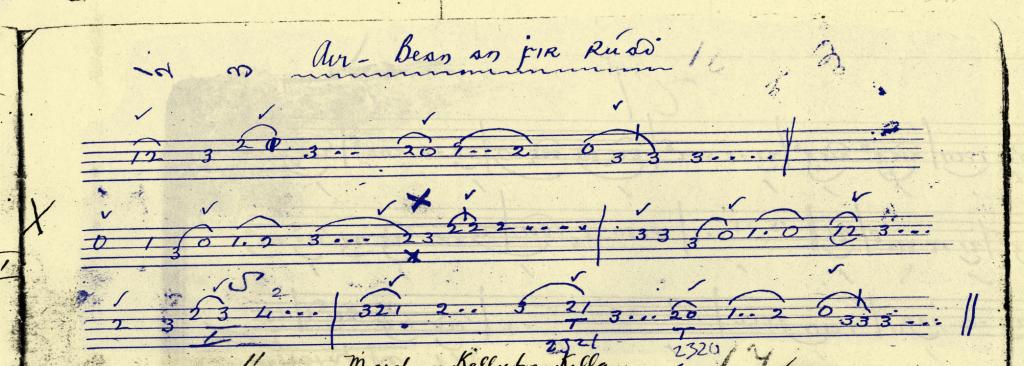

Bean an Fhir Rua

https://www.irishtune.info/tune/2231/

Found in Pádraig O’Keeffe’s manuscripts, and Dermot Hanifin recalls it was one that Pádraig was especially known for. Sadly, we don’t have a recording of him, but Matt Cranitch gives us a gorgeous rendition. This melody is also sometimes called An Cailín Deas Rua, but there are a whole slew of songs with similar names, and tunes that are similar or unrelated or somewhere inbetween (see commentary here), and disentangling them is more than I’m prepared to do.

The Blackbird

https://www.irishtune.info/tune/165/

The Blackbird is a very well-known and widespread air, played throughout Ireland. The title refers to Prince Charles Stuart and the Jacobite war of 1688, but the tune may be older. Related melodies are played as a set dance, hornpipe, and reel. Denis Murphy played the air on The Star Above the Garter, and it can be found in O’Keeffe’s manuscripts.

There are a whole host of related melodies, one of which is the hornpipe sometimes called The Stranger or Pol Hapenny. Below, Jerry McCarthy plays the air Spailpín a Rúin, which is, at least to my ear, very similar:

The Blue Danube

https://www.irishtune.info/tune/3781/

The Danube appears again! In their liner notes, the Monks of the Screw say this tune comes from Pádraig O’Keeffe by way of his student Jack “The Lighthouse” O’Connell who is said to have had a remarkably extensive repertoire of waltzes. The ITMA possesses two O’Keeffe manuscript records of this tune. One is from O’Keeffe’s student “Paddy ‘Páitín’ O’Connell of Cordal” and follows the two parts of the waltz usually played today. The other, from the Mrs. Katie Horan (nee O’Brien) collection, includes some extra bars which seem to be an adaptation of the more famous “An der schönen blauen Donau”, composed by Johann Strauss II in 1866. The Strauss tune was immensely popular then as now, and perhaps some of O’Keeffe’s pupils specifically requested it. Additionally, as referenced above, there may be a particular affinity for things Danubian in Sliabh Luachra.

The Bluemont

https://www.irishtune.info/tune/2816/

Written by American fiddler Rodney Miller in honor of the long-running contra dance in Bluemont, Virginia, this is probably a questionable entry to this list. However, Jackie Daly’s adoption of this tune has secured its place in the Sliabh Luachra repertoire.

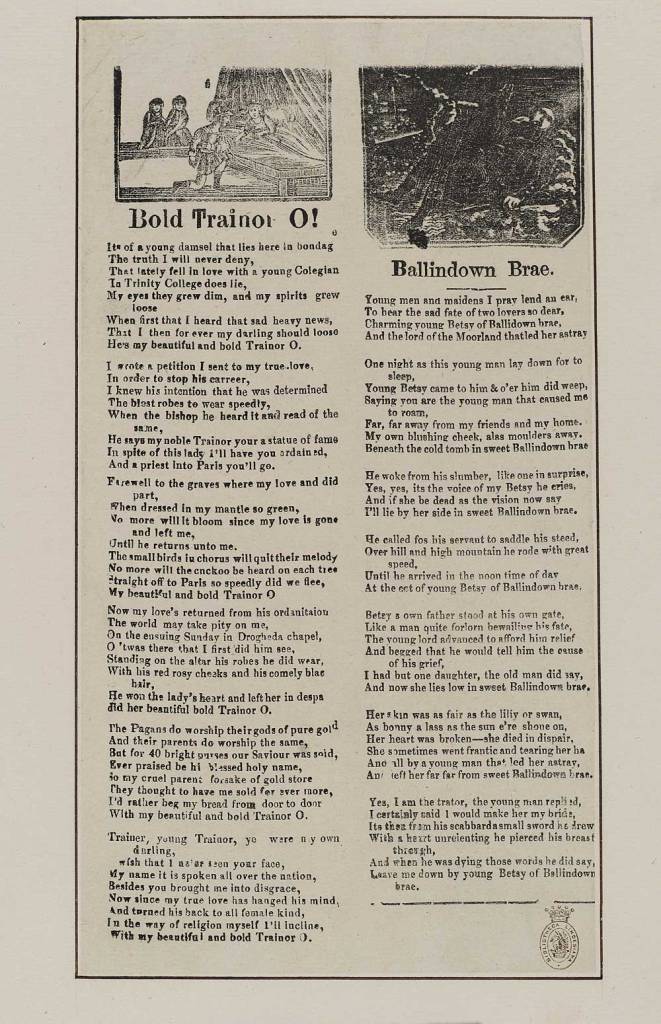

The Bold Trainor O

https://www.irishtune.info/tune/189/

Though this might be more commonly associated with the playing of Willie Clancy of county Clare, Julia Clifford recorded a lovely setting of it. One might be tempted to assume she got it from Pádraig originally, but in the Music from Sliabh Luachra pamphlet, we read that “Julia learned this air from the singing of her mother and does not associate it with Pádraig.” It seems to have been a popular and widespread ballad, printed as a broadside in the 19th century, and probably was equally known in Clare and Kerry and beyond. Versions can be found in O’Neill’s Waifs and Strays of Irish Melody (1922) p. 41 and the Bunting Collection. The melody is associated with two other songs: Uilleagan Dubh O and the Napoleonic ballad The Green Linnet.

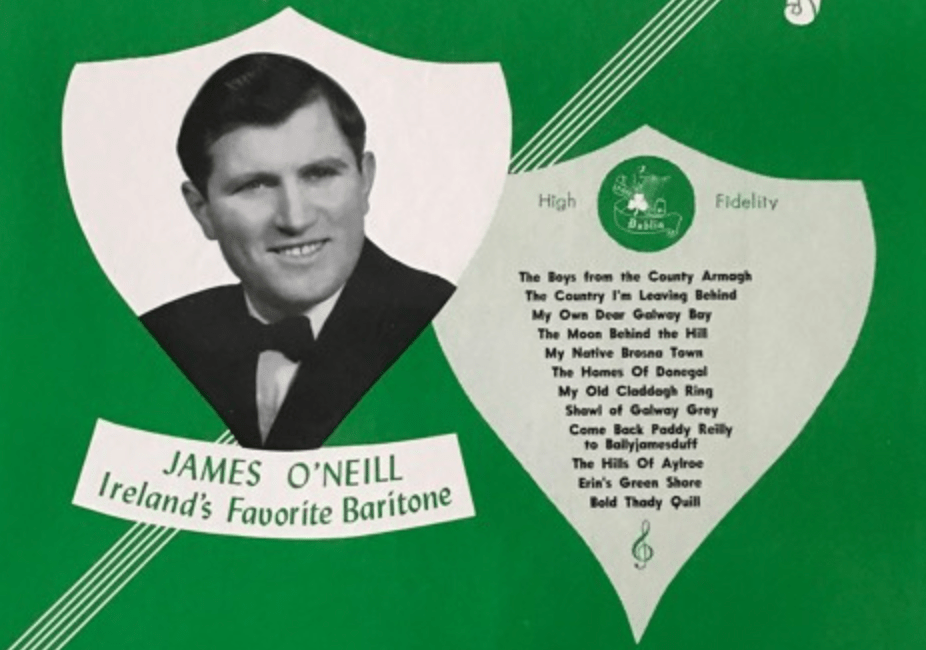

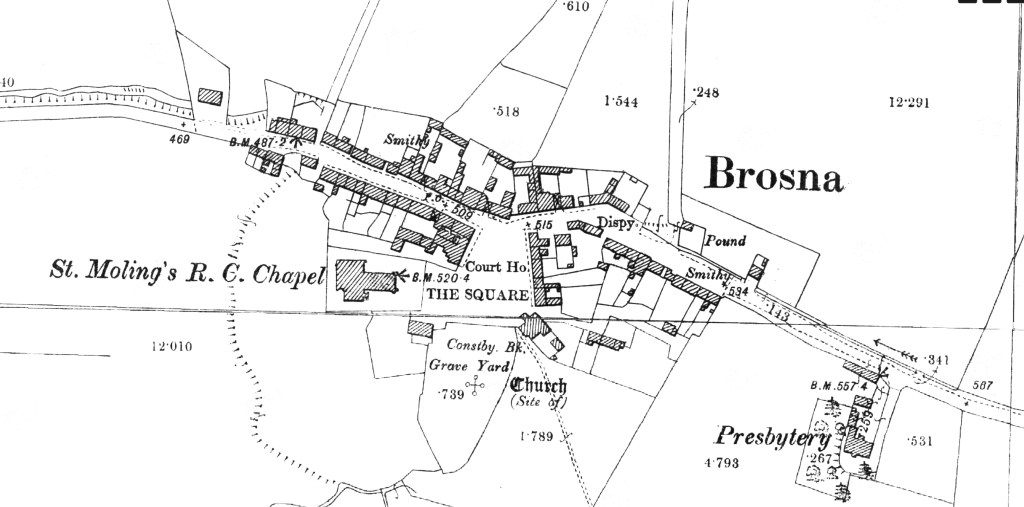

Brosna Town

https://www.irishtune.info/tune/3794/

Two tunes for the price of one! “My Native Brosna Town” was penned in 1957 by Daniel J. Hannon, a Brosna native who emigrated to New York as a young man. His song captures the particular flavor of wistful, rose-colored nostalgia that mid-century Irish-Americanism relished. The song’s popularity spanned the Atlantic, however, and his hometown came to fully embrace it as a local anthem. However, there are two melodies to which the song is sung nowadays, and it’s unclear if one is the real deal and the other an imposter, or if they share the credit equally. They are both cut from the same cloth as a number of other homely Irish sentimental songs. As with Sweet Kingwilliamstown or The Kilnamartyra Emigrant, just hearing the melody of this song (whichever you think it is) is sure to evoke the feeling of a place.

Oh my dear old home, ’neath the Kerry hills, My thoughts are still with thee,

Although I’m in a foreign land, Across the deep blue sea;

I’d long to stand, outside your door, And watch the sun go down,

And hear the church bells tolling, O’er my native Brosna Town.

By the old wood road, I’d long to stroll, With its hedges tall and green,

By Hannon’s gate I would debate, With some lovely fair colleen;

Or to take a walk, to Gurney’s Bridge, On a Sunday afternoon,

Where oft I danced a polka set, To the fiddler’s lively tune.

Old Carraigaleensha’s winding bend, And fancy too, I see,

The River Feale flows fast and clear, ’Round Murphy’s elder tree;

Where many a romance was discussed, From dark until the dawn,

And where I spent many a happy hour, With my own darling colleen bawn.

On Knockaclarig’s famed hilltop, I hope to stand once more,

I’ll view from Shannon Airport, To the town of sweet Rathmore;

Back from the peaks of Cuddy’s Reeks, To Killorglin on the Laune,

From Castlemaine to Coolegraine, And home to Brosna Town.

Now to conclude, I’ll say God bless, You mother and Ireland too,

I’ll ne’er forget, when both of you, Just faded from my view;

But soon I will, return again, And good times, we’ll put down

In that dear old home, by the old woodroad, Three miles from Brosna Town.

An Buachaill Caol Dubh

https://www.irishtune.info/tune/2589/

Pádraig O’Keeffe was said to have been especially known for his performance of this air, yet unfortunately there’s no recording of such. The melody, also associated with the song An Caisideach Bán, was collected by Petrie who noted that he believed it to be older than the “unworthy” song associated with it, but one might chalk this up to his Victorian sensibilities. The words, attributed to 18th century Munster poet Seán “Aerach” Ó Seanacháin, describe the personification of drink as the Dark Slender Boy (a glass of dark beer or bottle of whiskey could fit the description). The song enumerates the temptations of alcohol in romantic, even erotic imagery, and offers no redemptive conclusion. Certainly a theme Pádraig O’Keeffe may have found resonant.

Nuair a théim ar aonach a’ ceannach éadaigh

‘S bíonn an éirnis agam im láimh,

Síneann taobh liom an buachaill caol dubh,

‘S cuireann caol-chrobh isteach im láimh.

Is gearr’n-a dhéidh sin go mbím go h-aerach,

Gan puinn dem chéill ‘s mé os cionn an chláir,

A’ díol na n-éileamh do bhíonn am chéasa,

Seacht mí gan léine’s an fuacht am chrá.

‘Sé an buachaill caol dubh fada, féileach,

Clisde, léigheanta, ‘s gur mhaith é a shnó,

Do chlaoidh i bpéin mé ‘s do mhill i n-éag mé,

Is d’fhág mé féinig ar beagán stóir.

Dhon Fhrainnc dá dtéinn, nó go cuan Binn Éadain,

No a’ dul don léim sin go h-lnis Mór,

Bionn an séithleach im dhiaidh ar saothar,

Mara mbeinn féin uaidh ach uair de ló.

Do casadh Aoibhill na Craige Léith’ orrainn,

A’gabháil na sli is do ghaibh liom baidh;

Is dúirt dá ngéillfeadh an buachaill caol dubh

Go dtúrfadh céad fear dó suas im áit.

Do labhair an caol-fhear go gonta géar lé,

Is dúirt ná tréigfeadh a charaid ghnáth,

Gur shiúil sé Éire tré choillte ‘s réitigh

Le cumann cléibh is le searc im dheuidh.

~

When I go to the market to make a purchase

And grasp the earnest money within my hand,

The dark slender boy still seeks and searches

Till he slips beside me sedate and bland.

It’s not long after my senseless laughter

Will reach the rafters, and I’m left prone

When I pay what’s owing, even though it’s snowing,

Seven months without a shirt I am going, my money gone.

An Buachaill Caol Dubh is tall and festive

Clever and learned, of comely mien

But he has left me and in pain bereft me

Of all my fortune, sheep and kine.

Were I to travel to France, no go Cuan Binn Eadair

Or back across to Inishmore

Swift as a swallow, my track he would follow,

Until on the morrow I would find him there

The fairy Queen of Thomond met us while roaming

Near the fray rock, and she told the lad

If he would me abandon, that she would grant him

A hundred topers to make him glad.

The slim boy answered in tones of banter

It was ne’er his fancy to lose a friend

Over hill and o’er hollow, my track he’d follow

A soak so mellow, until the end.

Caoine Uí Domhniall

https://www.irishtune.info/tune/1083/

A caoine, anglicized as keen, is a wordless lament. In bygone days it was the practice at a wake for a set of mourners, sometimes hired for the task, to perform what P.W. Joyce described as a “startlingly wild and pathetic melody” which seems to have been at least partly improvised on the spot but also adhering to some set of structural norms. We have no real documentation of what these funerary keens sounded like, but I suspect the the instrumental airs called caoineadh are not related melodically so much as thematically. Unlike many slow airs, these are not melodies to songs but purely musical compositions.

Caoine Uí Domhniall laments the death of Aodh Ruadh Ó Domhnaill who led, and ultimately lost, the Nine Years’ War against English forces at the end of the 16th century. He died a year after his defeat at the Battle of Kinsale. It’s an open question whether this melody is quite so old, or was composed later. Contrary to my assertion above, there may be a melodic allusion to keening in the distinctive tumbling descent of notes in this melody, or it may indicate it came through the harping tradition and was influenced by that instrument, or both. O’Keeffe and his students Denis Murphy, Julia Clifford, and Paddy Cronin all recorded this air.

It is often the case that the performer of an air will tell a story about its meaning, so that the audience will have a deeper understanding of its import. It is not always in the form of an academic history or biography of the nominal subject, but more often akin to a bit of folklore. For instance, Pádraig and Denis both tell the story of a young man (presumably O’Donnell but who knows?) murdered with a pair of poisoned dancing shoes, and subsequently mourned by the Banshee.

Caoine Uí Néill

https://www.irishtune.info/tune/2721/

The subject of this lament is probably, but not definitively, Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone, who was Hugh O’Donnell’s principle ally in the Nine Years’ War. Seamus Ennis recorded Pádraig O’Keeffe playing it in 1945, and Pádraig seems to be the earliest source we have of this tune.

Créde Ó Chiarraí Luachra

The goddess Danu appears again! Of his composition, Bryan O’Leary writes: “I composed this piece and named it ‘Créde Ó Chiarraí Luachra’ in honour of an old ancient lore story in Sliabh Luachra based around the Paps mountains in A.D. 250. The story can be found in Dan Cronin’s book titled In the Shadow of the Paps.”

Denise

https://www.irishtune.info/tune/3780/

Composed by Timmy O’Connor and named for Denise Dalton, a Killarney fiddle player now living in Vancouver, B.C., who was a frequent visitor to the long-running Scully’s session before its sad discontinuation in the time of COVID.

Farewell to Dónal Óg

This is Paddy Jones‘ own G minor version of the well-known song air Dónall Óg. Paddy composed his setting while lamenting the loss of his first cousin Danny Jones who passed away before his time. Paddy also played the more usual setting beautifully but stopped for years after his cousin’s death. Paddy Jones was a firm believer in the central role of slow airs in the Sliabh Luachra tradition, and he had quite a number in his playbook, many of which he adapted from sources far afield. However, he invariably applied his inimitable blend of creativity and reverence for the local style, and played with an intensity of purpose, so that whatever melody he borrowed from elsewhere became his own.

Ger Dan Mac’s

https://www.irishtune.info/tune/7229/

Timmy O’Connor and the Monks of the Screw recorded this tune and Timmy credits it to “melodeon player and dancer Ger Dan McAulliffe who lived across the valley from my own place. My good friend and dancing teacher Larry Lynch from San Francisco collected a number of local sets from Ger Dan Mac and has been teaching them around the world over the last few decades. These sets are also included in his book Set Dances of Ireland.”

I’ll Meet You On a Day That Never Ends

Bryan O’Leary writes: “I wrote this tune in honour of all the people who have sadly passed on during this pandemic and the frontline workers who have helped to keep so many alive.”

Johnny Mickey Barry’s

https://www.irishtune.info/tune/7237/

A strange one, with a meandering and restless melody that never seems to settle down until the last note. Barry was a crucial link between the music of Tom Billy Murphy and younger generations; Timmy O’Connor and Jackie Daly are quick to credit his influence.

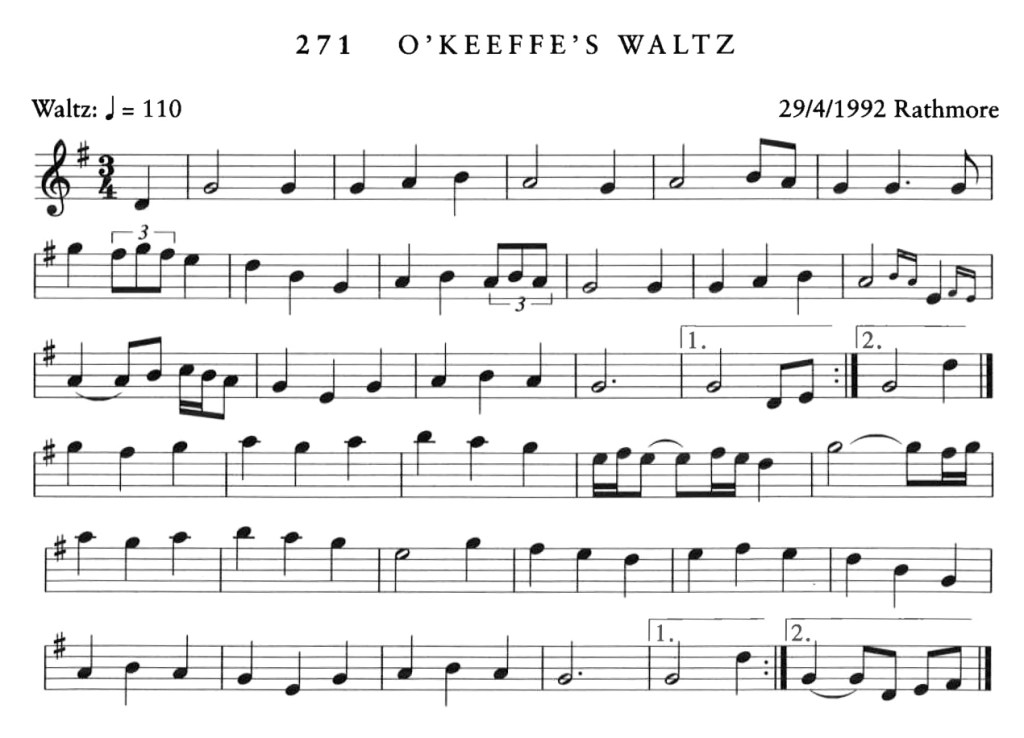

O’Keeffe’s

One of only three waltzes in Johnny O’Leary’s book, I don’t think this has shown up on a commercial recording yet. A nice enough little tune — what did it do to be shunned like this?

Lament for O’Sullivan

This seems to be a rare one. Kevin Delaney recorded Denis Murphy playing this during a field recording expedition in 1972. I haven’t found any other recorded examples in Sliabh Luachra or elsewhere, but it might be a (very different) setting of the Lament for Morty (Óg ) O’Sullivan found in the Goodman collection. There’s quite a detailed and gripping backstory which can be found in the Traditional Tune Archive.

Marysheen Went to Bonán

https://www.irishtune.info/tune/2828/

Bryan O’Leary tells us: “This waltz was a great favourite of Jimmy Doyle, and the song to the same air called ‘Mary She Went to Bonane’ was a great favourite of Jimmy O’Brien. They had a deal that whichever one of them would pass away first, the other would play or sing this at the others graveside. Jimmy O’Brien passed away in October 2021 and Jimmy Doyle Doyle fulfilled the promise by playing this waltz at Jimmy’s burial in Aghadoe, Killarney.”

From muscrai.wordpress.com: This song was composed by Johnny Nóra Aodha Twomey, one of a group of poets who lived in the Kilgarvan area, just across the border from Cúil Aodha. Marysheen was a daughter of the poet’s neighbour and had spent some time in America. The poet’s attempts at courting her were doomed, and she left for Bonán to marry Foxy Thade. [note: Johnny Twomey also wrote the song The Tailor Bán, recorded by Seamus Creagh.]

Ye muses I crave your attention, While I sing you a verse of a song,

And indeed it is not my intention, To keep you awaiting too long.

For you know since this game went against me, I can nevermore sleep until dawn,

My spirit completely has left me, Since Marysheen went to Bonán

A long time we had been acquainted, The space being exactly two years,

I took up the matter quite easy, Expecting that there was no fear,

But suspecting that I was a schemer, And wanted my favours withdrawn,

To rack and to smack and to tease me, They left her go back to Bonán.

‘Tis many’s the evening I wandered, And faced for the west I was prone.

To see me both racing and prancing, ‘Though very much wanting at home.

‘Tis many’s the garden I trampled, And fences I knocked in Diarmán

I’ll give up my palaver with Yankees, Since Marysheen went to Bonán.

‘Twas often I drank with her father, Full many’s the saucepan of beer

Fair days in Kenmare and Kilgarvan, Sure nothing could part us my dear.

He used to be praising his daughters, And saying they were handsome and calm,

How fair and severe it went after, When they left her go back to Bonán.

‘Tis often in deep conversation, Our language was plain and discreet,

But I was building on sandy foundations, Which soon slipped away from my feet;

Well knowing that some drops I was taking, And often out late ’til the dawn

She packed up her boxes quite easy, And she went for her frak to Bonán.

This Yankee had lots of good nature, And tried to make all things complete.

She never employed any spakers, Though one of them came there last week.

There was one from a shop that’s convenient, And one from our grand Tailor Bán,

Sure that put her prancing and racing, And hastened her back to Bonán.

‘Tis often we were at a tea party, With dainties both warm and sweet

Tasting and feasting ’til morning, Surrounded with all things complete.

I gave them a share of fine palaver, And made about twenty rabhcáns,

Pleasing and teasing them after, When they rattled her back to Bonán.

This Yankee had lots of good nature, And very well able to speak,

Although she was watching and waiting, ‘Til she lost all her patience and indeed.

For she travelled New York and Chicago, And drank a few treats in Gúgán,

No chap except Jack ever pleased her, ‘Til she met Foxy Thade from Bonán.

Below, Mikey Duggan plays this waltz which he learned from his neighbor and relation Ellie Spillane.

Ellen (née O’Sullivan) Spillane of Knockrour, East Scartaglin, was a concertina and fiddle player who was a formative influence on his music. Both Mike and Ellie’s son John were students of Pádraig O Keeffe as well.

Moonlight on the Yellow River

https://www.irishtune.info/tune/3795/

Another one from the playing of Jack the Lighthouse. It seems to have a whiff of American old-timeyness in the melody and the title. There is a river that flows near Cork City called Owenabue (Abhainn Buí meaning Yellow River) but another contender is the Allow, an important waterway in north Cork for which the barony of Duhallow is named. It’s not much of a leap from Allow to Yellow. Then again, maybe the tune or the title come from outside of the region. Probably unrelated, but the poet Ezra Pound wrote this short poem in the form of an epitaph:

And Li Po also died drunk.

He tried to embrace a moon

In the Yellow River.

The Old Man Rocking the Cradle

https://www.irishtune.info/tune/2634/

A very old and very well-travelled melody, it seems to have started out as a song (at least old enough to show up as a 19th-century broadside) which spiralled into a whole family of songs on the same theme: an older husband lamenting the fact that his young wife is out gallivanting every night while he is stuck at home rocking the baby whose patrilineage he is starting to doubt. Joe Heaney, Paddy Tunney, and Seamus Ennis have been recorded singing it, and Johnny Doherty both sings the song and plays the air in his recording. Versions and variants can be heard all over the British and Irish islands, Australia, and North America. One well known version is an Irish-language lullaby with ties to southern Munster: “Bog Braon Don tSeanduine” (which seems to conflate the old man and the baby!) There are also similarities to other lullabies such as Seoithín Seo-hó.

As is often the case, it’s unclear if the melody we now associate with the song was created at the same time, or if the words were sung to a pre-existing tune. In this instance it’s quite likely they were together from the beginning–the melody can be found with the same title in Goodman’s collection which dates to about the same time the broadsides were printed. Either way, the air is now fairly inseparable from the theme of the song, perhaps due to the distinct lullaby-like quality of the melody. The tune can sometimes be heard played simply in waltz time (and there are jig and polka relatives out there!), but it seems to have really caught on with instrumentalists as a “descriptive piece.” This is the treatment given by Pádraig O’Keeffe in his famous rendition. In fact, for such a widespread song and tune, it is remarkable how it is so closely associated with Pádraig more than any other musician (though Leo Rowsome, John Kelly Senior, and Paddy Taylor all recorded admirable versions). This can probably be attributed to Pádraig’s virtuosic and spellbinding performance of the piece, eliciting a wide range of interpretations: a sweet-natured lullaby, a mournful lament, a vaudevillian party trick… throwing in a snippet of the Foxhunter’s Jig for good measure. However, as distinct as Pádraig’s setting may be, it can’t be attributed to his individual genius alone. In fact, it was already known to be played in just such a manner when Chief O’Neill wrote in 1910:

Few (have been) born in Ireland who have not heard of the song named “Rocking the Cradle,” or, as it is sometimes called, “Rocking a Baby that’s None of My Own.” Both song and air are now almost entirely forgotten, and it was a matter of no little difficulty to get a setting of the music. In preference to an unsatisfactory version of my own, we selected a setting found in an American publication of over fifty years ago. A fair version was also printed in Smith’s Irish Minstrel, published in 1825 at Edinburgh. It was quite a trick to play this piece to suit the old Irish standard of excellence, in which the baby’s crying had to be imitated on the fiddle. To bring out the tones approaching human expression, the fiddle was lowered much below concert pitch. The performer held firmly between the teeth one end of a long old-fashioned door key with which at appropriate passages the fiddle bridge was touched. This contact of the key produced tones closely imitating a baby’s wailing. Miss Ellen Kennedy, who learned the art from her father, a famous fiddler of Ballinamore, County Leitrim, was very expert in the execution of this difficult performance.

This is exactly what Pádraig did: retuning the low G string down to a lower D to bring out more resonance in the instrument and allow for interesting double-stops, and performing exactly this trick with a heavy brass key held in his teeth. (Some say it was the key to Glountane School, having never returned it after his unceremonious retirement.) Interestingly, of all the airs associated with Pádraig, this is one his students generally did not go on to perform themselves. In fact, one of the few fiddlers I know of to have attempted the full performance is Gerry Harrington, who manages it brilliantly, both with and without the aid of the key.

Pull Down the Blinds

https://www.irishtune.info/tune/7236/

The song “Pull Down the Blind” began as music hall song written and composed by Charles McCarthy in the 1860s. The melody gained popularity enough to spread it all over Ireland, but the Sliabh Luachra setting, which can be heard in the playing of Timmy O’Connor and his Newmarket crew, is not the usual one associated with this name, though it’s certainly related. Cuz Teahan remembered a sort of hybrid version, notated in the book Sliabh Luachra on Parade.

Did you ever make love? If not, have a try.

I courted a girl once, so bashful and shy,

A fair little creature, who, by the by,

At coaxing and wheedling had such a nice way;

Ev’ry night to her house I went

In harmless delight our evenings were spent,

She had a queer saying, whatever she meant,

For whenever I entered the house she would say:

Cho: Pull down the blind, love, pull down the blind,

Pull down the blind, love, come don’t be unkind;

Though we’re alone, bear this in mind

Somebody’s looking, love, pull down the blind.

O’Rahilly’s Grave

https://www.irishtune.info/tune/1478/

https://www.irishtune.info/tune/5749/

In September of 1948, Seamus Ennis recorded Pádraig O’Keeffe playing this air, and this seems to be the earliest recording we have of the melody. On the label of the acetate it is listed as O’Rahilly’s Grave (Lament for Aodghán Ó Rathaille). It has been claimed that of all his extensive repertoire of airs, this was one of Pádraig’s favorites, and it may be that its relative obscurity was part of why he treasured it. However, Junior Crehan of the County Clare recalled hearing it sung when he was a young boy, and though he was unable to learn the words, having not much Irish, he played the air in later life in a setting nearly identical to Pádraig’s. In his telling, the song was connected to the story of a priest who had taken a wife and was banished to live above the Cliffs of Moher. In fact, Junior was so enamored with the tune that he fashioned it into a hornpipe as well, and called it Caslean an Oir.

When Denis Murphy was recorded playing this air in 1960, on Smithsonian Folkways’ Traditional Music of Ireland, Vol. 2: Songs and Dances from Down, Kerry, and Clare, he played a very similar version (though his high note is garishly sharp, IMHO.) Curiously, when Julia Clifford came to record the air for The Star Above the Garter, she played a significantly different B part from Pádraig’s setting. Exactly why, we may never know, but subsequently there are now two distinct settings, and at least judging by its representation on commercial recordings, Julia’s version seems to be more popular. (…but to speak subjectively for another moment, of the settings mentioned here, I think Pádraig’s is the superior melody, going to the high plaintive, not shrill, 3rd, and then the octave jumping 7th in the following phrase. Just my 2p.)

The subject of the lament, Aodghán Ó Rathaille, is a famous poet from Sliabh Luachra. You can read more than you may have ever wanted to know in this biographical essay from the Journal of Cumann Luachra. If we can believe Junior Crehan, there were once words to the song, but whether they consisted of a threnody mourning the loss of O’Rahilly or recounted the tale of a married priest, we may never know. In any case, the melody tells a moving story of grief and mourning, perhaps more eloquently than words ever could.

Listening to Pádraig’s, Denis’, Julia’s, and Jerry’s recordings together, you can identify the different settings, but it’s also a great illustration of the stylistic differences in their playing.

An Raibh tú ag an gCarraig?

https://www.irishtune.info/tune/812/

This is one of the most popular slow airs throughout Ireland, but it is thought to have Munster connections, and was certainly a favorite of Julia Clifford and the rest of her cohort. The title translates to “Were you at the rock?” and like a number of other Irish-language songs, the words may or may not be intended to convey a double meaning. It may be a straightforward love song, or there may be symbology at work. Certainly there is a history of double-meaning in songs as a way of circumventing anti-Irish laws in the time of occupation. “The rock” in question has been suggested to mean the “mass rock” of the type used secretly as the altar in the Catholic mass when it was banned by English law.

On the other hand, there is some evidence that indicates that this meaning was imposed retroactively on the straightforward romantic lyrics. O’Neill’s source claims that the song (including, presumably, the melody) was composed by the 18th century Tyrone bard Dominic O’Mongan, in honor of one Eliza Blacker, a noblewoman of Carrick, Armagh. If that is the case, it remains a mystery (to me, anyway) how this came to be thought of as a Munster tune.

Julia plays the air on The Star Above the Garter, and it is likely she learned it from Pádraig. Though it is almost always played in the minor mode, some early transcriptions have it in a major key.

The River Maine

A very new entry to the repertoire, this is a composition of Scartaglin musician and impresario, P.J. Teahan. He named it for the river which rises in Tobermaing (where P.J.’s father was born) and glides serenely through Castleisland on its way to meet the Atlantic at Castlemaine.

Sweet Donoughmore

https://www.irishtune.info/tune/3235/

Sometime around 1960, Pádraig O’Keeffe played this air for Raidió Teilifís Éireann. Considering this was just a few years before his death, it’s a lovely performance. He also included it in a number of his teaching manuscripts.

Donoughmore is in the Barony of Muskerry, not geographically part of Sliabh Luachra, but nearly adjacent. There must have been a song called Sweet Donoughmore that used this melody, but information is scanty and I haven’t been able to track it down (but see notes to The Banks of Sullane above.) The Irish language song Cath Chéim an Fhia (attributed to Cork poet Máire Bhúi Ní Laoghaire) also uses this melody, but probably the most popular song to use the air is The Kilnamrtyra Exile, written by Johnny Brown of that village (also in Muskerry) who left to fight in the First World War and later served as a missionary in Africa. It’s interesting that the three associated songs are all connected to a relatively small area of County Cork. It’s not outlandish to imagine Pádraig might have had this from the singing of his mother Margaret O’Callaghan, from Doonasleen, Cork.

Sweet Kingwilliamstown

https://www.irishtune.info/tune/3870/

The melody has been used for a few different songs, including “An Goirtín Eórnan” and “An Buachaill Rua”, but most famously for the song attributed to Daniel Buckley (1891-1918), a native of Ballydesmond (known during British occupation as Kingwilliamstown), a survivor of the Titanic disaster, and the last recorded American soldier to die in action in France in WWI. Julia Clifford and others have played it, but it was a particular favorite of Maurice O’Keeffe.

My bonny barque floats light and free, across the surging foam

It bears me far from Innis Fail to seek a foreign home

A lonely exile driven ‘neath misfortune’s cruel frown

From my own home and friends so dear in sweet Kingwilliamstown.

Whilst here upon the deck I stand and watch the surging foam

Kind thoughts arise all in my mind of friends I’ll ne’er see more

Of moonlit eves, and happy hours – how fast the tears roll down

Still thinking of my friends so dear, round sweet Kingwilliamstown.

Shall I no more gaze on that shore or view those mountains high

Or stray along Blackwater’s banks where I roamed as a boy

Or view the sun o’er Knocknaboul light up the heather brown

Before she flings her farewell beams o’er sweet Kingwilliamstown.

I know not yet, but fondly hope, where ‘er my footsteps roam

To cherish deeply in my heart the thoughts and love of home

Now fades the shore and on my soul the night winds sadly down

So God be with you Ireland, farewell Kingwilliamstown.

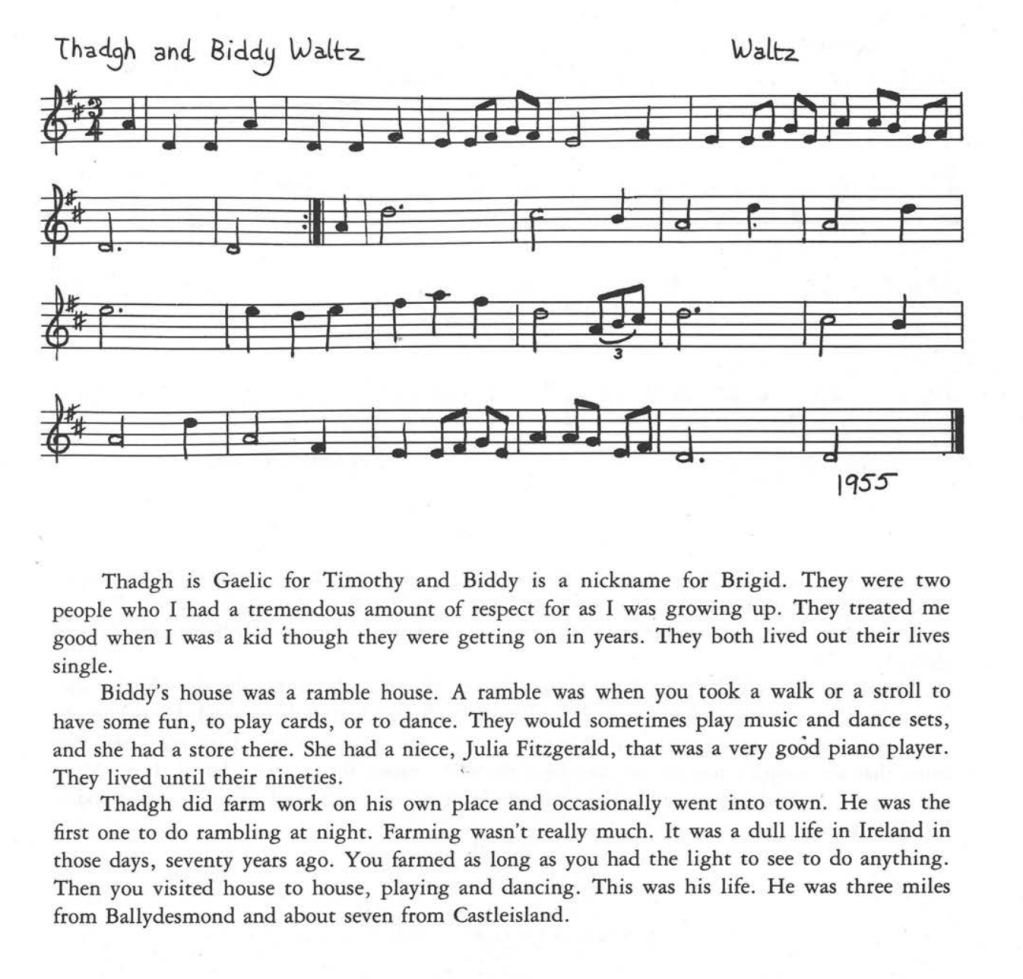

Tadhg and Biddy

https://www.irishtune.info/tune/6314/

Another fairly recent composition from the Teahan family, this is a Cuz Teahan tune named for two fondly recalled neighbors from his childhood in Castleisland.

Táimse im’ Chodladh

https://www.irishtune.info/tune/3109/

An ancient and popular air throughout Ireland which dates at least as far back as its first printing in the early 18th century but is probably older, and perhaps of Scottish origin. The song, also quite old, is in the mode of an aisling in which the spirit of Ireland, personified as a beautiful woman, implores the singer (and by extension, the listener) to awaken from slumber, arise, and take up arms against the invader. The phrase “From Carrick-on-Suir west to the banks of Dingle” lends credence to the assertion that it was written by a Munster poet (though perhaps based upon, or referencing, an older Scottish Jacobite poem). The air is associated with the old harp and pipe traditions, and this may be an example of a tune that was played to arouse patriotic feelings at times when singing in the Irish language was dangerous. If there is indeed a Munster provenance, it seems to have persisted there: it can be found in Goodman’s collection, O’Keeffe’s manuscripts, and in the 1970s Maida Sugrue recorded the song and Julia Clifford, the air.

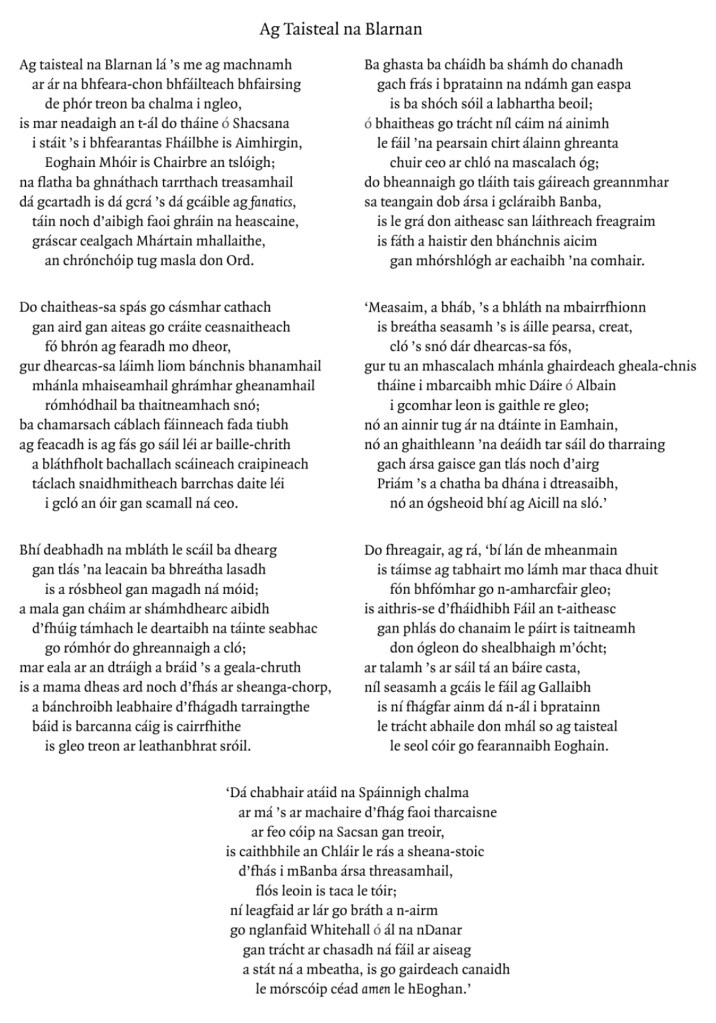

Ag Taisteal na Blarnan

https://www.irishtune.info/tune/48/

Jackie Daly, a firm believer in the importance of slow airs in the Sliabh Luachra tradition, recorded this in 1995. The title (Traveling Through Blarney) comes from the aisling by 18th century poet Eoghan Rua Ó Súilleabhain, a figure whose stature in the local folklore is one of the few to rival that of O’Keeffe. Like Pádraig, he is famed at least as much for his roguish exploits as for his art, and you can read a comprehensive biography here, or a more local remembrance of the man from the Journal of Cumann Luachra. He was born and died in Meentogues, Gneeveguilla, barely a stone’s throw from the farms later occupied by Johnny O’Leary and the Weaver Murphys. The story goes that Ó Súilleabhain was working as a spailpin for a farmer near Blarney, County Cork. One day, on overhearing the people of the house discussing poetry, he offered an opinion and was laughed at. To put them in their place Eoghan composed this poem with complex metric and rhyming patterns. He set the poem to an older air, collected by Bunting as Staca An Mhargaidh, and found in the Goodman collection as well. That song also seems likely to have deep Munster roots.

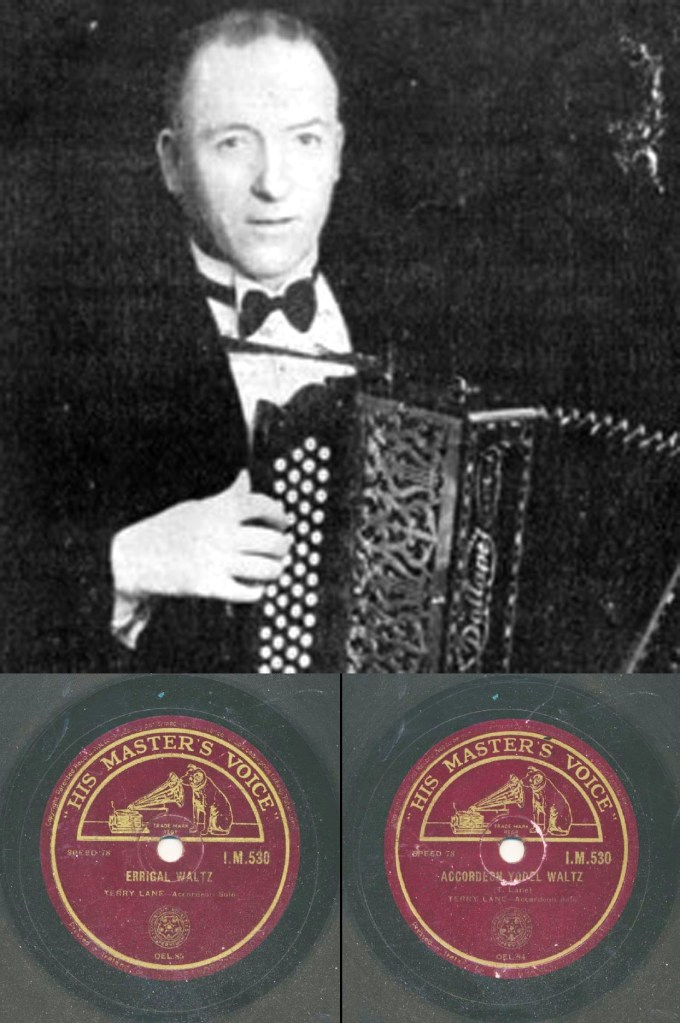

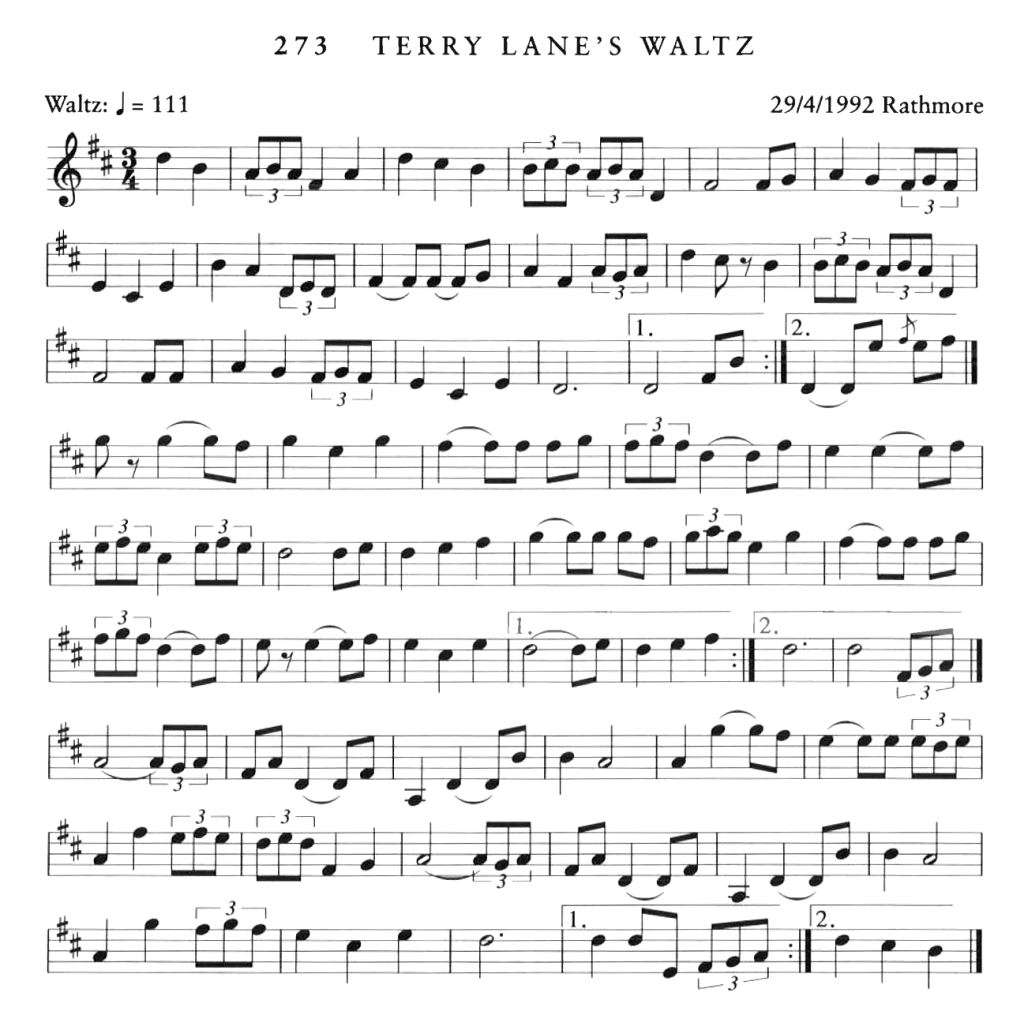

Terry Lane’s

https://www.irishtune.info/tune/7273/

Terry Lane was an accordion player from Cavan active in in the 1930s and 40s who ended up in Dublin and cut a number of 78s with his eponymous Ceilidh Band and The Dublin Metropolitan Garda Ceili Band, as well as some solo recordings. In 1938 he put out The Accordion Yodel Waltz (thanks to Jeff Ksiazek at the Ward Music Archives for help tracking this down!) I don’t know of any direct connection with Sliabh Luachra, so presumably this 78 found its way into Johnny O’Leary’s hands and he adopted the waltz. It’s a fun, careening sort of tune and one can imagine the fun Johnny had with it.

Tom Billy’s

https://www.irishtune.info/tune/7235/

The Monks of the Screw tell us this comes from the repertoire of Mick Duggan, who in turn said he received it from Tom Billy Murphy. It can also be found in O’Keeffe’s teaching manuscripts, and it’s one of the lonely three waltzes to appear in Johnny O’Leary’s book. It’s especially interesting for the very very high D it hits in the second part, which is easy enough on the accordion, but necessitates moving into a new position on the fiddle (or as O’Keeffe’s notation seems to suggest, to play it with the sixth finger!), and might be a bridge too far for the flutes, whistles, and pipes. However, this hasn’t affected its popularity very much, and it can still be heard with some regularity in Sliabh Luachra sessions today.